One of the most important things to understand about machines is their life-cycle. In this subsection, you will learn:

- Introduction to the machine life-cycle

- About enlistment

- About commissioning machines

- About allocation and deployment

Introduction to the machine life-cycle

Everything that happens to a machine under MAAS control conforms to a specific life-cycle. All MAAS machines are in a named state, or in transition between states. Most of these transitions are user-controlled. Only the “failure” state is reached under the direction of MAAS, when a user’s request for certain state changes can’t be successfully completed.

In general, the various states and transitions can be summarised in a diagram:

The central state flow at the bottom of the diagram is the “standard” life-cycle. If all goes well, you won’t have to deviate much from this flow:

-

Machines start as servers in your environment, attached to a network or subnet that MAAS can reach and manage. If those machines are configured to netboot, MAAS can discover them and enlist them, assigning a status of “NEW”. By definition, NEW machines are: (2) enabled to network boot, and (2) on a subnet accessible to MAAS.

-

Once you’ve pared the list to machines that you want MAAS to control, you can choose to commission them. You can select any machine that is marked “NEW” and tell MAAS to commission it, or, if you add machine manually, MAAS will automatically commission it. Commissioning PXE boots the machine and loads an ephemeral version of the Ubuntu operating system into the machine’s RAM. MAAS then uses that OS to scan the machine to determine its hardware configuration: CPUs, RAM, storage layouts, PCI and USB devices, and so forth. Commissioning can be customised – more on that in a later section. If a machine fails to properly commission, either because of a commissioning error, or because the commissioning process timed out, that machine enters a “FAILED” state.

-

MAAS next tests the machine to make sure it’s working properly. These basic tests just assure that the discovered hardware works as expected. Testing can also be customised, if you wish. Machines that don’t pass these tests are moved to a “FAILED” state.

-

Having tested it, MAAS then places that machine in the “READY” state, meaning that MAAS should be able to deploy it, based on the gathered hardware information.

-

Before you deploy a machine, you should allocate it. This step essentially involves taking ownership of the machine, so that no other users can deploy it.

-

Having allocated a machine, you can deploy it. When deploying, MAAS again loads an ephemeral Ubuntu OS onto the machine, uses

curtinto configure the hardware in the way you’ve specified, and then loads and boots the OS image you’ve requested. Deployment also runs somecloud-initsteps to finish machine configuration, before leaving it up and ready for use.

Once deployed, there are a couple of minor state changes you can effect without releasing the machine:

-

You can lock a machine, if desired, to provide a little extra insurance that it won’t accidentally be changed by you – or anyone.

-

Depending upon the machine’s duty cycle, you can also power it on, power it off, or even power-cycle it (to effect a reboot, for example).

Note that these minor state changes are not shown in the diagram above. There are also some exceptional states you can command:

-

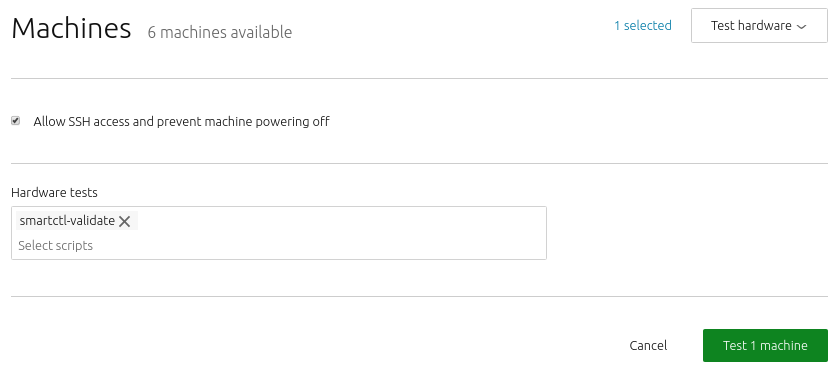

For any machine that is ready, allocated, or deployed, you can cycle it through a battery of tests at any time. Be aware, of course, that testing causes the machine to be unavailable for normal use for the duration of the text cycle.

-

Machines that are ready, allocated, or deployed can also be placed in “rescue mode”. Essentially, rescue mode is the same as walking to a malfunctioning or mis-configured machine, taking it off the network, and fixing whatever may be wrong with it – except that you’re doing so via SSH, or by running tests from MAAS, rather than standing in front of the machine. Machines in rescue mode can’t enter normal life cycle states until you remove them from rescue mode. You can, of course, delete them, modify their parameters (tags, zone, and so on), power them off, and mark them broken. Rescue mode is like a remote repair state that you can control from wherever you are.

-

Machines that are allocated or deployed can also be marked broken. A broken machine powers off by default. You can still power it on, delete it, or enter rescue mode, but you can’t log into it via SSH. This state is intended for machines that experience catastrophic hardware or software failures and need direct repairs.

There is one more state that a machine can get into: “failed”. This state is entered when commissioning, allocation, or deployment are not successful. Getting out of a failed state means figuring out what went wrong, correcting it, and retrying the failed operation. For example, when a machine fails, you can try and commission it again, hopefully after you’ve found the bug in your custom commissioning script that’s causing it to fail (for instance).

Now that we have a solid overview of the life-cycle, let’s break down some of these states and transitions in greater detail.

About enlistment

MAAS is built to manage machines, including the operating systems on those machines. Enlistment and commissioning are features that make it easier to start managing a machine – as long as that machine has been configured to netboot. Enlistment enables users to simply connect a machine, configure the firmware properly, and power it on so that MAAS can find it and add it.

Enlistment happens when MAAS starts; it reaches out on connected subnets to locate any nodes – that is, devices and machines – that reside on those subnets. MAAS finds a machine that’s configured to netboot (e.g., via PXE), boots that machine into Ubuntu, and then sends cloud-init user data which runs standard (i.e., built-in) commissioning scripts. The machine actually adds itself over the MAAS API, and then requests permission to send commissioning data.

Since MAAS doesn’t know whether you might intend to actually include these discovered machines in your cloud configuration, it won’t automatically take them over, but it will read them to get an idea how they’re set up. MAAS then presents these machines to you with a MAAS state of “New.” This allows you to examine them and decide whether or not you want MAAS to manage them.

When you configure a machine to netboot – and turn it on while connected to the network – MAAS will enlist it, giving it a status of “New.” You can also add a machine manually. In either case, the next step is commissioning, which boots the machine into an ephemeral Ubuntu kernel so that resource information can be gathered. You can also run custom commissioning scripts to meet your specific needs.

About the enlistment process

When MAAS enlists a machine, it first contacts the DHCP server, so that the machine can be assigned an IP address. An IP address is necessary to download a kernel and initrd via TFTP, since these functions can’t accept domain names. Once the machine has a bootable kernel, MAAS boots it:

Next, initrd mounts a Squashfs image, ephemerally via HTTP, so that cloud-init can execute:

Finally, cloud-init runs enlistment and setup scripts:

The enlistment scripts send information about the machine to the region API server, including the architecture, MAC address and other details. The API server, in turn, stores these details in the database. This information-gathering process is known as automatic discovery or network discovery.

Typically, the next step will be to commission the machine. As an alternative to enlistment, an administrator can add a machine manually. Typically this is done when enlistment doesn’t work for some reason. Note that when you manually add a machine, MAAS automatically commissions the machine as soon as you’ve added it.

After the commissioning process, MAAS places the machine in the ‘Ready’ state. ‘Ready’ is a holding state for machines that are commissioned, waiting to be deployed when needed.

MAAS runs built-in commissioning scripts during the enlistment phase. When you commission a machine, any customised commissioning scripts you add will have access to data collected during enlistment. Follow the link above for more information about commissioning and commission scripts.

About BMC enlistment

For IPMI machines, you only need to provide IPMI credentials. MAAS automatically discovers the machine and runs enlistment configuration by matching the BMC address. For non-IPMI machines, you must specify a non-PXE MAC address. MAAS automatically discovers the machine and runs enlistment configuration by matching the non-PXE MAC address.

About adding machines

There are two ways to add a machine to MAAS:

-

If you place the machine on a connected network, and the machine is configured to netboot, MAAS will automatically enlist it.

-

If you add a machine manually, MAAS will automatically commission it. There are also ways to turn off this automatic commissioning, should you desire to do so.

MAAS typically adds a machine via a combination of DHCP, TFTP, and PXE. By now, you should have enabled MAAS to automatically add devices and machines to your environment. This unattended method of adding machines is called enlistment.

Configuring a computer to boot over PXE is done via its BIOS, often referred to as “netboot” or “network boot”. Normally, when you add a machine manually, MAAS will immediately attempt to commission the machine. Note that you will need to configure the underlying machine to netboot, or commissioning will fail. MAAS cannot handle this configuration for you. While the correct method for configuring network boot depends heavily on your server, there are two common elements:

-

The network card on your server must be able to support PXE, i.e., your NIC – whether independent or integrated on a motherboard – must have a boot PROM that supports network booting. You’ll need to consult the documentation for the machine in question to determine this. Note that in MAAS versions before 2.5, you are required to provide the MAC address of the PXE interface when adding a new machine manually.

-

You usually have to interrupt the boot process and enter the BIOS/UEFI menu to configure the network card’s PXE stack. Again, you may need to consult your machine’s documentation to pin down this step.

Additional steps will vary widely by machine type and architecture.

Regardless of how MAAS adds a machine, there are no special requirements for the underlying machine itself, other than being able to netboot. In particular, there is no need to install an operating system on it.

About cloning machines

MAAS 3.1 provides the ability to quickly clone or copy configuration from one machine to one or more machines, via the MAAS UI, providing convenient access to an existing API feature… This is a step towards machine profile templating work.

Creating a machine profile is a repetitive task. Based on the responses to our survey – and multiple forum posts, we have learned that most users create multiple machines of the same configuration in batches. Some users create a machine profile template and loop them through the API, while some create a script to interface with the CLI. However, there is no easy way to do this in the UI except by going through each machine and configuring them individually.

MAAS API already has the cloning functionality, but it was never exposed in the UI. Hence, users may not know that this API feature exists, nor is there any current documentation about how to use this feature. Although the current cloning API feature does not solve all machine profile templating problems, it is a great place for us to start moving in the direction of machine templates.

About copying machine configurations

As a MAAS user – API or UI – you may want to copy the configuration of a given machine and apply it to multiple existing machines. Assuming that at least one machine is already set to the desired configuration, you should be able to apply these same settings to a list of destination machines. This means that a user should be able to:

- select the source machine to copy from.

- validate that the source machine exists.

- select at least 1 destination machine.

- validate that the destination machine(s) exist.

- edit the source machine or destination machines, if needed.

- know at all times which machines are affected.

- see the cloned machines when cloning is successful, or

- get clear failure information, if cloning fails.

About choosing configuration items to copy

As a MAAS user, you will likely want to select whether storage, network, or both configurations should be cloned. The cloning API allows users to choose interfaces and storage separately. Thus, this new feature should allow the user to:

- clone only the interface (network) configuration.

- clone only the storage configuration.

- clone both configurations.

About cloning restrictions

In order for cloning to succeed, a few restrictions must be met:

- The destination interface names must be the same source.

- The destination drive must be equal to or larger than the source drive.

- For static IPs, a new IP will be allocated to the interface on the destination machine

Cloning machines is available starting with MAAS version 3.1.

About enlisting deployed machines

In general, when adding a machine to MAAS, it network boots the machine into an ephemeral environment to collect hardware information about the machine. While this is not a destructive action, it doesn’t work if you have machines that are already running a workload.

For one, you might not be able to disrupt the workload in order to network boot it. But also, the machine would be marked as Ready, which is incorrect.

When adding a machine, you may specify that the machine is already deployed. In that case, it won’t be going through the normal commissioning process and will be marked as being deployed.

Such machines lack hardware information. In order to update the information, a script is provided to run a subset of the commissioning scripts and send them back to MAAS.

Because already-deployed machines were not deployed by MAAS, most of the standard MAAS commands will not affect the machine and may, at times, return some odd results. This is not errant behaviour; the goal of enlisting deployed machines is to avoid disturbing their workload.

MAAS version 3.0 cannot enlist deployed machines. Please upgrade to MAAS version 3.1 or greater to gain this capability.

MAAS version 2.9 cannot enlist deployed machines. Please upgrade to MAAS version 3.1 or greater to gain this capability.

About commissioning machines

When MAAS commissions a machine, the following sequence of events takes place:

- DHCP server is contacted

- kernel and initrd are received over TFTP

- machine boots

- initrd mounts a Squashfs image ephemerally over HTTP

- cloud-init runs built-in and custom commissioning scripts

- machine shuts down

The commissioning scripts will talk to the region API server to ensure that everything is in order and that eventual deployment will succeed.

MAAS chooses the latest Ubuntu LTS release as the default image for commissioning. If desired, you can select a different image in the “Settings” page of the web UI, by selecting the “General” tab and then scrolling down to the Commissioning section.

Commissioning requires 60 seconds.

About commissioning NUMA and SR-IOV nodes

If you are using the NUMA architecture, MAAS versions 2.7 and higher guarantee that machines are assigned to a single NUMA node that contains all the machine’s resources. Node boundaries are critical, especially in vNUMA situations. Splitting nodes can create unnecessary latency. You want the NUMA node boundaries to match VM boundaries if at all possible.

You must recommission NUMA/SR-IOV machines that were previously commissioned under version 2.6 or earlier.

When using these nodes, you can specify a node index for interfaces and physical block devices. MAAS will display the NUMA node index and details, depending upon your configuration, to include the count of NUMA nodes, number of CPU cores, memory, NICs, and node spaces for bonds and block devices. You can also filter machines by CPU cores, memory, subnet, VLAN, fabric, space, storage, and RAID, among others.

About MAAS commissioning scripts

MAAS runs scripts during enlistment, commissioning and testing to collect data about nodes. Both enlistment and commissioning run all builtin commissioning scripts, though enlistment runs only built-ins. Commissioning also runs any user-uploaded commissioning scripts by default, unless the user manually provides a list of scripts to run. MAAS uses these commissioning scripts to configure hardware and perform other tasks during commissioning, such as updating the firmware. Similarly, MAAS employs hardware testing scripts to evaluate system hardware and report its status.

Scripts can be selected to run from web UI during commissioning, by testing hardware, or from the command line. Note that MAAS only runs built-in commissioning scripts during enlistment. Custom scripts can be run when you explicitly choose to commission a machine. A typical administrator workflow (with machine states), using customised commissioning scripts, can be represented as:

Add machine -> Enlistment (runs built-in commissioning scripts MAAS) -> New -> Commission (runs built-in and custom commissioning scripts) -> Ready -> Deploy

NOTE: Scripts are run in alphabetical order in an ephemeral environment. We recommend running your scripts after any MAAS built-in scripts. This can be done by naming your scripts 99-z*. It is possible to reboot the system during commissioning using a script, however, as the environment is ephemeral, any changes to the environment will be destroyed upon reboot (barring, of course, firmware type updates).

When a machine boots, MAAS first instructs it to run cloud-init to set up SSH keys (during commissioning only), set up NTP, and execute a script that runs other commissioning scripts. Currently, the sequence of MAAS-provided commissioning scripts proceeds like this:

-

maas-support-info: MAAS gathers information that helps to identify and characterise the machine for debugging purposes, such as the kernel, versioning of various components, etc. Runs in parallel with other scripts.

-

maas-lshw: this script pulls system BIOS and vendor info, and generates user-defined tags for later use. Runs in parallel with other scripts.

-

20-maas-01-install-lldpd: this script installs the link layer discovery protocol (LLDP) daemon, which will later capture networking information about the machine. This script provides some extensive logging.

-

maas-list-modaliases: this script figures out what hardware modules are loaded, providing a way to autorun certain scripts based on which modules are loaded. Runs in parallel with other scripts.

-

20-maas-02-dhcp-unconfigured-ifaces: MAAS will want to know all the ways the machine is connected to the network. Only PXE comes online during boot; this script brings all the other networks online so they can be recognised. This script provides extensive logging.

-

maas-get-fruid-api-data: this script gathers information for the Facebook wedge power type. Runs in parallel with other scripts.

-

maas-serial-ports: this script lists what serial ports are available on the machine. Runs in parallel with other scripts.

As of MAAS version 3.0, 40-maas-01-network-interfaces is no longer used by MAAS.

- 40-maas-01-network-interfaces: this script is just used to get the IP address, which can then be associated with a VLAN/subnet.

- 50-maas-01-commissioning: this script is the main MAAS tool, gathering information on machine resources, such as storage, network devices, CPU, RAM, details about attached USB and PCI devices, etc. We currently pull this data using lxd: We use a Go binary built from lxd source that just contains the minimum source to gather the resource information we need. This script also checks whether the machine being commissioning is a virtual machine, which may affect how MAAS interacts with it.

- 50-maas-01-commissioning: this script is the main MAAS tool, gathering information on machine resources, such as storage, network devices, CPU, RAM, etc. We currently pull this data using lxd: We use a Go binary built from lxd source that just contains the minimum source to gather the resource information we need. This script also checks whether the machine being commissioning is a virtual machine, which may affect how MAAS interacts with it.

-

maas-capture-lldp: this script gathers LLDP network information to be presented on the logs page; this data is not used by MAAS at all. Runs in parallel with other scripts.

-

maas-kernel-cmdline: this script is used to update the boot devices; it double-checks that the right boot interface is selected.

Commissioning runs the same dozen or so scripts as enlistment, gathering all the same information, but with these caveats:

-

Commissioning also runs user-supplied commissioning scripts, if present. Be aware that these scripts run as root, so they can execute any system command.

-

Commissioning runs test scripts which are not run during enlistment.

-

Commissioning scripts can send BMC configuration data, and can be used to configure BMC data.

-

The environment variable BMC_CONFIG_PATH is passed to serially run commissioning scripts; these scripts may write BMC power credentials to BMC_CONFIG_PATH in YAML format, where each key is a power parameter. The first script to write BMC_CONFIG_PATH is the only script allowed to configure the BMC, allowing you to override MAAS’ built-in BMC detection. If the script returns 0, that value will be send to MAAS.

-

All built-in commissioning scripts have been migrated into the database.

-

maas-run-remote-scriptsis capable of enlisting machines, so enlistmentuser-datascripts have been removed. -

The metadata endpoints

http://<MAAS>:5240/<latest or 2012-03-01>/andhttp://<MAAS>:5240/<latest or 2012-03-01>/meta-data/are now available anonymously for use during enlistment.

In both enlistment and commissioning, MAAS uses either the MAC address or the UUID to identify machines. Currently, because some machine types encountered by MAAS do not use unique MAC addresses, we are trending toward using the UUID.

To commission a node, it must have a status of “New”.

You have the option of setting some parameters to change how commissioning runs:

-

enable_ssh: Optional integer. Controls whether to enable SSH for the commissioning environment using the user’s SSH key(s). ‘1’ == True, ‘0’ == False. Roughly equivalent to the Allow SSH access and prevent machine powering off in the web UI. -

skip_bmc_config: Optional integer. Controls whether to skip re-configuration of the BMC for IPMI based machines. ‘1’ == True, ‘0’ == False. -

skip_networking: Optional integer. Controls whether to skip re-configuring the networking on the machine after the commissioning has completed. ‘1’ == True, ‘0’ == False. Roughly equivalent to Retain network configuration in the web UI. -

skip_storage: Optional integer. Controls whether to skip re-configuring the storage on the machine after the commissioning has completed. ‘1’ == True, ‘0’ == False. Roughly equivalent to Retain storage configuration in the web UI. -

commissioning_scripts: Optional string. A comma separated list of commissioning script names and tags to be run. By default all custom commissioning scripts are run. Built-in commissioning scripts always run. Selectingupdate_firmwareorconfigure_hbawill run firmware updates or configure HBA’s on matching machines. -

testing_scripts: Optional string. A comma separated list of testing script names and tags to be run. By default all tests taggedcommissioningwill be run. Set tononeto disable running tests. -

parameters: Optional string. Scripts selected to run may define their own parameters. These parameters may be passed using the parameter name. Optionally a parameter may have the script name prepended to have that parameter only apply to that specific script.

About machine commissioning logs

MAAS keeps extensive logs of the commissioning process for each machine. These logs present an extremely detailed, timestamped record of completion and status items from the commissioning process.

About disabling individual boot methods

It is possible to disable individual boot methods. This must be done via the CLI. When a boot method is disabled MAAS will configure MAAS controlled isc-dhcpd to not respond to the associated boot architecture code↗. External DHCP servers must be configured manually.

To allow different boot methods to be in different states on separate physical networks using the same VLAN ID configuration is done on the subnet in the UI or API. When using the API boot methods to be disabled may be specified using the MAAS internal name or boot architecture code↗ in octet or hex form.

For MAAS 3.0 and above, the following boot method changes have been implemented:

- UEFI AMD64 HTTP(00:10) has been re-enabled.

- UEFI ARM64 HTTP(00:13) has been enabled.

- UEFI ARM64 TFTP(00:0B) and UEFI ARM64 HTTP(00:13) will now provide a shim and GRUB signed with the Microsoft boot loader keys.

- grub.cfg for all UEFI platforms has been updated to replace the deprecated

linuxefiandinitrdeficommands with the standardlinuxandinitrdcommands. - GRUB debug may now be enabled by enabling rackd debug logging.

Disabling boot methods is available in MAAS version 3.0 or greater.

About automatic script selection by hardware type

When selecting multiple machines, scripts which declare the for_hardware field will only run on machines with matching hardware. To automatically run a script when ‘Update firmware’ or ‘Configure HBA’ is selected, you must tag the script with ‘update_firmware’ or ‘configure_hba’.

Similarly, scripts selected by tag on the command line which specify the for_hardware field will only run on matching hardware.

About script results

A script can output its results to a YAML file, and those results will be associated with the hardware type defined within the script. MAAS provides the path for the results file in an environment variable, RESULT_PATH. Scripts should write YAML to this file before exiting.

If the hardware type is storage, for example, and the script accepts a storage type parameter, the result will be associated with a specific storage device.

The YAML file must represent a dictionary with these two fields:

-

result: The completion status of the script. This status can bepassed,failed,degraded, orskipped. If no status is defined, an exit code of0indicates a pass while a non-zero value indicates a failure. -

results: A dictionary of results. The key may map to a results key defined as embedded YAML within the script. The value of each result must be a string or a list of strings.

Optionally, a script may define what results to return in the YAML file in the metadata fields… The results field should contain a dictionary of dictionaries. The key for each dictionary is a name which is returned by the results YAML. Each dictionary may contain the following two fields:

-

title- The title for the result, used in the UI. -

description- The description of the field used as a tool-tip in the UI.

Here is an example of “degrade detection”:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# --- Start MAAS 1.0 script metadata ---

# name: example

# results:

# memspeed:

# title: Memory Speed

# description: Bandwidth speed of memory while performing random read writes

# --- End MAAS 1.0 script metadata ---

import os

import yaml

memspeed = some_test()

print('Memspeed: %s' % memspeed)

results = {

'results': {

'memspeed': memspeed,

}

}

if memspeed < 100:

print('WARN: Memory test passed but performance is low!')

results['status'] = 'degraded'

result_path = os.environ.get("RESULT_PATH")

if result_path is not None:

with open(result_path, 'w') as results_file:

yaml.safe_dump(results, results_file)

About tags and scripts

As with general tag management, tags make scripts easier to manage; grouping scripts together for commissioning and testing, for example:

maas $PROFILE node-script add-tag $SCRIPT_NAME tag=$TAG

maas $PROFILE node-script remove-tag $SCRIPT_NAME tag=$TAG

MAAS runs all commissioning scripts by default. However, you can select which custom scripts to run during commissioning by name or tag:

maas $PROFILE machine commission \

commissioning_scripts=$SCRIPT_NAME,$SCRIPT_TAG

You can also select which testing scripts to run by name or tag:

maas $PROFILE machine commission \

testing_scripts=$SCRIPT_NAME,$SCRIPT_TAG

Any testing scripts tagged with commissioning will also run during commissioning.

About debugging script failures

You can individually access the output from both completed and failed scripts.

If you need further details, especially when writing and running your own scripts, you can connect to a machine and examine its logs and environment.

Because scripts operate within an ephemeral version of Ubuntu, enabling this option stops the machine from shutting down, allowing you to connect and probe a script’s status.

As long as you’ve added your SSH key to MAAS, you can connect with SSH to the machine’s IP with a username of ubuntu. Type sudo -i to get root access.

About testing hardware

If you wish, you can tell MAAS to test machine hardware using well-known Linux utilities. MAAS can test machines that have a status of Ready, Broken, or Deployed. You can include testing as part of the commissioning process. When you choose the ‘Commission’ action, MAAS will display the dialog described below. Be aware, though, that if the hardware tests fail, the machine will become unavailable for Deployment.

The majority of testing scripts only work with machines that are backed by physical hardware (e.g. they may be incompatible with VM-based machines).

With MAAS, you can easily write, upload and execute your hardware testing scripts and see the results.

About machine hardware & test logs

MAAS logs test results and allows you to view a summary of tests run against a particular machine. You can also example details on any particular tests:

You can also examine the “raw” log output:

Help interpreting these logs can be found under the Logging section of this documentation.

About testing machine networking

MAAS provides a comprehensive suite of network and link testing capabilities. MAAS can check whether or not links are connected, detect slow links, and report link and interface speeds via UI or API. In addition, you can test Internet connectivity against a user-provided list of URLs or IP addresses. Bonded NICS will be separated during this testing, so that each side of a redundant interface is fully evaluated.

Network testing also includes customisable network testing and commissioning scripts. There are no particular restrictions on these scripts, allowing you to test a wide variety of possible conditions and situations.

About post-commission configuration

Once commissioned, you can configure the machine’s network interface(s). Specifically, when a machine’s status is either “Ready” or “Broken”, interfaces can be added/removed, attached to a fabric and linked to a subnet, and provided an IP assignment mode. Tags can also be assigned to specific network interfaces.

About allocation and deployment

Once a machine has been commissioned, the next logical step is to deploy it. Deploying a machine means, effectively, to install an operating system on it, along with any other application loads you wish to run on that machine.

A detailed picture of deployment looks something like this:

Before deploying a machine, MAAS must allocate it (status ‘Allocated’). Allocating a machine reserves the machine for the exclusive use of the allocation process. The machine is no longer available to any other process, including another MAAS instance, or a process such as Juju.

The agent that triggers deployment may vary. For instance, if the machines are destined to run complex, inter-related services that scale up or down frequently, like a “cloud” resource, then Juju↗ is the recommended deployment agent. Juju will also install and configure services on the deployed machines. If you want to use MAAS to install a base operating system and work on the machines manually, then you can deploy a machine directly with MAAS.

Machines deployed with MAAS will also be ready to accept connections via SSH, to the ‘ubuntu’ user account. This connection assumes that you have imported an SSH key has to your MAAS account. This is explained in SSH keys.

Juju adds SSH keys to machines under its control.

MAAS also supports machine customisation with a process called “preseeding.” For more information about customising machines, see How to customise machines.

To deploy, you must configure the underlying machine to netboot. Such a machine will undergo the following process, outlined in the above diagram:

- MAAS boots the machine via the machine’s BMC, using whatever power driver is necessary to properly communicate with the machine.

- The booted machine sends a DHCP Discover request.

- The MAAS-managed DHCP server (ideally) responds with an IP address and the location of a MAAS-managed HTTP or TFTP boot server.

- The machine uses the HTTP/TFTP location to request a usable Network Boot Program (NBP).

- The machine recieves the NBP and boots.

- The machine firmware requests a bootable image.

- MAAS sends an ephemeral OS image, including an initrd; this ephemeral (RAM-only) image is necessary for

curtinto carry out any hardware-prep instructions (such as disk paritioning) before the deployed OS is booted. - The initrd mounts a SquashFS image, also ephemerally, over HTTP.

- The machine boots the emphemeral image.

- The ephemeral image runs

curtin, with passed pre-seed information, to configure the machine’s hardware. - The desired deployment (target) image is retrieved by

curtin, which installs and boots that deployment image. Note that the curtin installer uses an image-based method and is now the only installer used by MAAS. Although the older debian-installer method has been removed, curtin continues to support preseed files. For more information about customising machines see How to customise machines. - The target image runs its embedded

cloud-initscript set, including any customisations and pre-seeds.

Once this is done, the target image is up and running on the machine, and the machine can be considered successfully deployed.

Also note that, before deploying, you should take two key actions:

-

Review and possibly set the Ubuntu kernels and the Kernel boot options that will get used by deployed machines.

-

Ensure any pertinent SSH keys are imported (see SSH keys) to MAAS so it can connect to deployed machines.